Stephanie Mathews: Converting Stinky Paper Waste into the Sweet Smell of Success

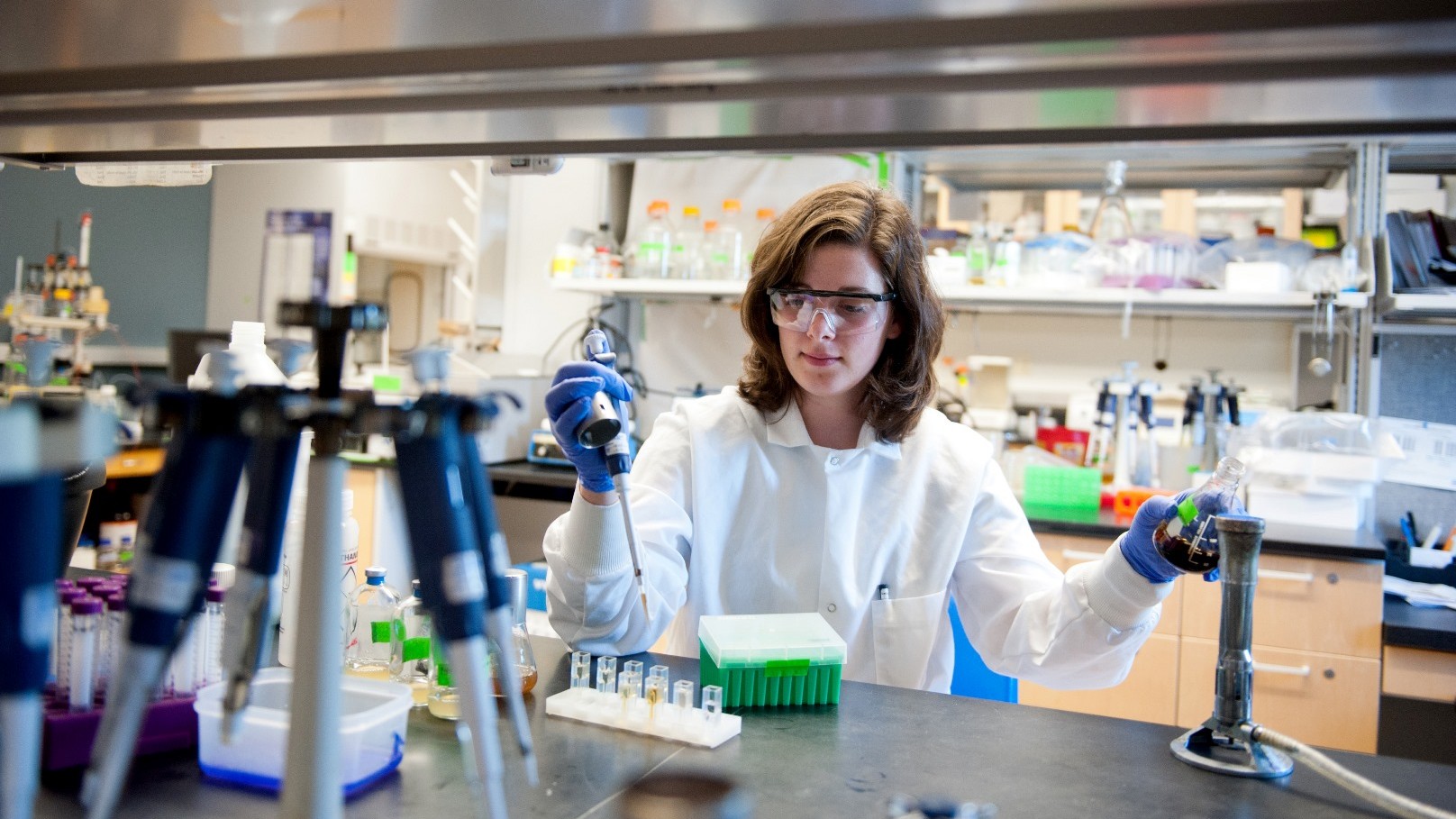

NC State graduate student Stephanie Mathews put her communications savvy to the test recently, proving she can relate scientific research in a clear, quick, and succinct way during Graduate Education Day at the N.C. General Assembly. Even when it stinks.

Mathews successfully got the ear of several legislators, who asked questions and sought more information. Her topic? “Recycling with Bacteria: Tiny Solutions for a Stinky Problem.”

What is the stinky problem? Mathews doesn’t exaggerate, but captivates when she describes the stinky subject of her studies. She drives home the crux of her research, something familiar to all who have driven past a paper mill: paper manufacturing’s tell-tale stench.

That stench is the impetus for Mathews’ research. And, imagine if you are a policy maker living in this state. North Carolina alone has more than 100 paper mills. Plot those mills onto a map, and the state is dotted with paper mill sites. Now, consider that North Carolina is only one of multiple states with paper manufacturing facilities.

Mathews, a doctoral candidate in microbiology, seized the moment, according to NC State Graduate School Dean Maureen Grasso. She observed that Mathews can successfully compress and translate years of work into two minutes flat if needed.

“It was an opportunity for a few of our researchers to present their work in a real-world context to policy makers,” says Grasso, who chose scholars who know how to succinctly present topical research. The scholars — Mathews, Amanda Walter and Doreen McVeigh — won honors for their posters at the March Graduate Student Research Symposium at McKimmon Center.

“There were several doctoral students involved, and all were outstanding. They stepped up and did well. Stephanie was a star,” Grasso said.

Wherever you find paper manufacturing, you will find the odiferous outcome known as black liquor.

“If you have ever driven by a paper mill town and smelled rotten eggs or boiling cabbage, you are familiar with paper mill waste,” Mathews explains in vivid terms. She is working on natural odor eaters, which can do even more than offset the offensive smell.

Her research involves the use of bacteria to transform black liquor, even making it useful in the production of other materials. “I like to think of this process as recycling with bacteria,” says Mathews.

“Stephanie broke down her technical research in ways that were clear and relevant — and meaningful. Several of our legislators were deeply interested,” says Grasso. “She got their attention.”

Of course, keeping things simple is not so simple. Mathews spent time refining the way she presented years of research on black liquor. She studied how to distill her message further at a science communications conference.

“One of the things we did was writing a short piece about our research. Then, we gave a pop talk, describing our research program in one minute. I worked to find a simple way to explain it,” she says.

Mathews broke her research into discrete pieces, addressing initial questions such as, “why do paper mills produce waste?”

(The short answer: Pulping is the process by which paper mills isolate the parts of trees useful in paper making from the less desirable components.)

In the process, Mathew guides listeners into the essences of her murky, stinky, research subject. Pulping requires chemicals, and black liquor is the byproduct.

“It is a dark-colored, stinky liquid waste. The disposal method of choice is to burn black liquor. Unfortunately, burning it means sharing its fragrance,” says Mathews.

“Long-term, we want to find a way to commercialize biological treatment of paper wastes. The piece of equipment responsible for burning black liquor is called the recovery boiler. It is the most expensive piece of equipment for a paper mill. If you want to increase production and don’t have that capacity, then you are limited,” she said.

Why does the process of papermaking stink in the first place? Mathews explains that the aromatics in the paper making process arise from degradation of wood molecules called lignin.

“Lignin is made up of aromatic groups which are hydrocarbons. The same structures can be found in crude oil,” she said.

Lignin, she adds, is the main component of black liquor but it is complex and messy. At present, paper mills typically burn black liquor and produce steam. “Steam is not the only end use for the lignin. I am making the case that lignin can be transformed into a desirable product.”

Her research demonstrates how soil bacteria may be used to eat black liquor. One bacterium “can consume black liquor and produce valuable chemicals as a result.” Those chemicals can be used in the making of products such as foam rubber, bottles or even fuel.

In the process, the bacteria could become tiny recycling factories, says Mathews.

She came to her research in a personal way, from the very first day of graduate school. Someone suggested there was a product called black liquor and asked what she might do with it. Mathews’ husband and family lived in Canton, a paper mill town.

“Almost everyone has an experience with a paper mill smell,” Mathews says. Her grandparents told her they remembered when the mill dumped the black liquor rather than burning it.

“The river would be black, and it was believed that it had special healing properties. A whole culture develops around a paper mill.”

She was asked to study something to bridge the gap between forestry bio products and microbiology. Mathews first spent some weeks reading about black liquor before she sought to isolate anything growing in the black liquor.

“It was mandated that black liquor can no longer be discharged, as it once was. Now they now burn it, and when you burn it—you can use the steam. But this would be better than using it for steam,” Mathews said.

This was Mathews’ first experience presenting her work to elected leaders.

“Quite a lot of them were very open. They wanted to understand what I was doing.” Among them was Sam Queen, who represents the Canton area.

“I had face time with four people who sat down and listened, and asked questions about process,” she said. She discussed her work with officials from Wake, Guilford and Haywood counties.

“I really felt like we should do this more; that was my strongest experience in discussing my research.”

Mathews will complete her doctoral work this summer. In addition to her Ph.D. work, she participated in the Graduate School’s Preparing the Professoriate program with her mentor Dr. Amy Grunden, professor of microbiology.

Mathews helped design and implement the 2014 Photosynthetic Bioreactor Summer High School Research program, a six-week summer training program for high school students interested in biofuels and research. The students were able to share their research through a poster session at the NC State Summer Undergraduate Research Symposium. Mathews hopes to continue her work in microbiology in academia.

- Categories: