Douglas Shoemaker

The Visionary: At The Computational Frontier, Envisioning Responsible Environmental Change

Douglas Shoemaker, who completed his doctorate this year, trained at NC State’s Center for Geospatial Analytics before accepting a directorship at the Center for Applied GIS at UNC-Charlotte on July 1 this year.

His forte is a meshing of ecology, geospatial analysis and time-space modeling. He uses “an ecosystem services lens to explore and quantify linkages between human and environmental systems, providing analyses of pressing global resource and sustainability concerns.”

Douglas Shoemaker, landscape ecologist, is one part pragmatic straight-talker, and one part visionary. He may make

a point citing the science fiction film Jurassic Park, or the work of a Nobel Laureate. He is passionately invested in

changing both the landscape we know and that of the future, working within what he calls the computational frontier.

“I focus on impactful publication and produce analyses that are contextually relevant, scientifically rigorous, and

legally and economically credible.”

Shoemaker tackled other frontiers before returning to academia. Despite his youthful appearance, he spent years in industry before exchanging a briefcase for a backpack full of books. Then, as now, he was equally invested in the natural

world, preferring to cycle rather than drive. He did not fit the traditional mold of doctoral students—for one thing, he is presently the parent of two teenage daughters (ages 19 and 16) as well as a son, age two.

Shoemaker’s studies while at NC State integrated ecology, geospatial analysis and time-space modeling. He describes using “an ecosystem services lens to explore and quantify linkages between human and environmental systems.” Dynamic spatial-temporal modeling, a tangible component of Shoemaker’s research, investigates urbanization and its impact on socio-ecological systems.

While the work sounds esoteric, it addresses the pressing issues of our time and influences public policy. Landscape ecology is an evolving science, one which studies the relationships between environments and ecological processes. In examining ecological processes, landscape ecologists consider spatial patterns as they occur in different landscapes.

They address both research and policy, with an eye to improving them.

MOVING FROM MANAGEMENT RANKS TO ADDRESSING THE BIG QUESTIONS OF OUR TIME

Shoemaker feels a need to reframe our questions about science. He isn’t a dystopian thinker, yet not a utopian either. He merges interdisciplinary studies in ecology, geospatial analysis and time-space modeling, and draws upon the work of economists and philosophers. His extensive experiences in the business world grounded him in practicalities — a

perspective he draws upon now. While climbing the tiers of upper management, he worked in large urban centers in northern Virginia and Boston. He “kept running into really smart people” in Boston—meaning, ones who were smart and degreed. Shoemaker was smart, successful, but not degreed.

“It bothered me,” he says frankly.

The fact that he had flunked out of undergraduate school rankled Shoemaker, despite his business achievements. He banked enough to return to school at age 39, graduating with honors. “I finished at University of Massachusetts at Boston in 2003 with a B.S. in Biology, summa cum laude. (But) I had a laugh thinking about my lab partner in Physics II…we had a

great time, but he was stunned to discover I was the same age as his dad!”

Shoemaker then entered graduate school at Florida, where he developed a method to measure the amount of climate-changing carbon dioxide absorbed by trees via analysis of satellite images.

Shoemaker accepted a research position at UNC-Charlotte’s Center for Applied Geographic Information Science and became acquainted with Ross Meentemeyer.

“I met Ross in 2005, interviewing for my first real job after getting my MS in Forestry from Florida.”

In 2013, Meentemeyer joined NC State’s Center for Geospatial Analytics, and Shoemaker followed, enrolling in the doctoral program. At NC State, Meentemeyer became his advisor.

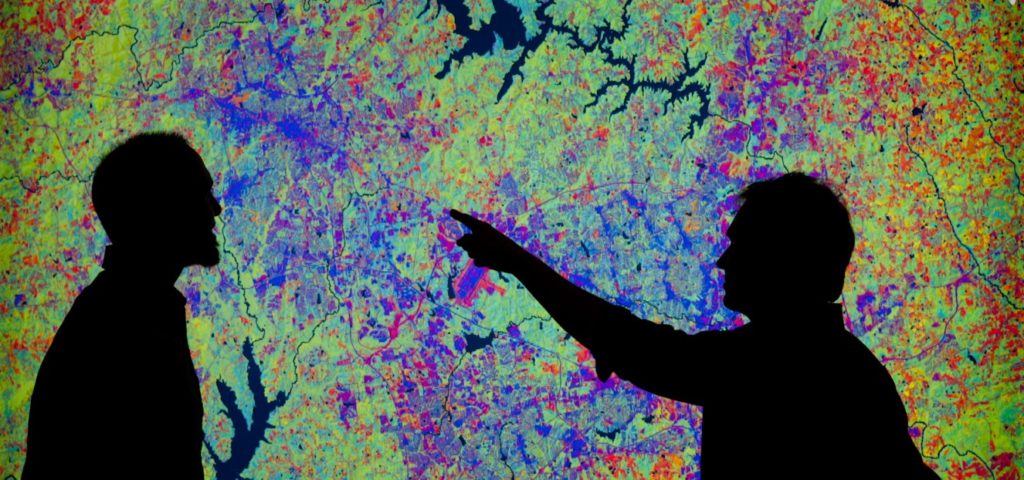

He has high praise for his mentee. “Doug is one of two students working on a new physical user interface that allows anybody to model and visualizes changes in landscapes, a software/hardware framework we call “Tangible Landscapes,” says Meentemeyer. “Think of Google Earth meets the playground sandbox: It scans the sand, and when you push the sand into a hill, that hill appears on the screen and in the map,” he explains.

“Doug is conscious of the interface design. He looks at why is it relevant and practical. He wants to make it easy to investigate whatever variables users think are important in the landscape, and after the system runs, be able to instantly visualize the trade-offs,” he says. “As scientists, we’re objective and we find multiple solutions to complex problems.

Sustainability is not about a single best answer: It’s about trade-offs.”

At the Center for Geospatial Analytics, spatially explicit, emergent models allow faculty and students to simulate problems as diverse as flooding, or ill-planned urban sprawl. The models use data to precisely and dynamically demonstrate the impact of a proposed highway, for example, or of a controlled burn, or of sea-surge on the coastal regions. Data—in a dynamic form—springs to life, becoming three-dimensional and relatable, rather than pages of charts, algorithms and statistics. Policy makers, for example, can witness authentic demonstrations of ecological impacts and virtual outcomes.

Shoemaker points out that two of North Carolina’s key economic interests, agriculture and tourism, depend upon one basic thing: fertile soil.

“Nothing works unless there is some widespread recognition of the role natural capital plays in our economic systems and our wellbeing. To sustain it, we see the need for fertile soil, clean water,” he says.

At NC State, Shoemaker was able to pursue interests in ecology and study how ecosystems changed over space and time.

On a personal level, there were more lessons concerning time. While in the business world, Shoemaker says, “I loved time management.” As a doctoral student at NC State, those skills were also put to the test. He commuted weekly from Charlotte, keeping a Raleigh apartment and juggling an active family life back in Charlotte. He is pleased that he powered through his dissertation and graduated in the spring of this year.

Shoemaker’s dissertation concerned the question, “what does a benign landscape look like?” He elaborates, describing his notion of just such an environment. “We live closer together, we build close to the tops of the hills, not down near the streams and wetlands. We use porous building materials. We process a lot of things on site. We compost. We process waste on site. If we don’t sprawl, we have plenty of room. You could take everyone on the planet and give them a garden apartment, and they would all fit in an area the size of Texas.”

“Amazingly, I did everything ‘on schedule’” he emailed in late June. “I successfully defended my dissertation, titled ‘The Role of Spatial Heterogeneity and Urban Pattern in Modulating Ecosystem Services’ in late March and graduated in early May.”

For Shoemaker, a Ph.D. is the ultimate brass ring, which he grabbed and held tight despite multiple challenges.

Shoemaker has successfully joined the “really smart people” ranks, he jokes. A sense of humor and a sense of a bigger vision has seen him through the journey.

“On planning the re-entry into academia, I engaged in a ‘limitless’ dream exercise where I asked myself what would I do every day if there were no barriers. After some thought, I settled on a conundrum that had held me, one where my favorite trout hole was right next to a road, the valleys being the only place for level roads and the low spot for water. The stream was being polluted by MTBE, the winter additive for gasoline in those days, and I realized that place, and specifically the location of roads and streams relative to each other, had to be understood in order for any successful protection of the water. My dream then was to explore the interplay between (physical and built) topographies and ecosystems, and report my findings so we as a society could protect our natural heritage.”

The dream he carried became reality.

“While all this was happening, I was able to apply for a half-dozen openings around the country,” says Shoemaker. “I was delighted to find a relative abundance of opportunities for my qualifications, which I understand is not the typical academic job-hunt reality. I made the final cut for three positions.” He chose the one which landed him back in Charlotte where his graduate studies first solidified.

“I will be Director of Research and Outreach at UNC-Charlotte, and spend much of my time conducting and communicating research, developing new ideas for research funding, and cultivating collaborations among the Center’s grad students, and, other internal and external faculty.”

Now, he envisions a world wherein proactive human agency works towards building the common wealth—or the common good. As a former New Englander, Shoemaker grew up with the everyday idea of a “common wealth” he says, and that has influenced his geopolitical reality.

For Shoemaker, there is an urgent need for this sort of meaningful discourse about human agency and the environment. In his expansive vision for the future, there is ample room and resources for everyone on planet Earth—that is, if we consider the common good. “Things can happen,” he says with conviction.

(Becky Kirkland photo)

Shoemaker mentions a scene in the film Jurassic Park in which a scientist played by actor Jeff Goldblum discusses chaos theory. The actor explains that chaos theory “deals with unpredictability in complex systems. The shorthand is the Butterfly Effect. A butterfly can flap its wings in Peking and in Central Park you get rain instead of sunshine.”

Then Goldblum sets out to demonstrate unpredictability by pouring water onto a hand, asking observers to predict which way the water will trickle. Will the water roll off her thumb, or finger? Will the water roll the same way, each time? He demonstrates the water changing course. “Why?” the fictitious scientist asks. “Because tiny variations, the orientation of

hairs on your hand, the amount of blood distending from your vessels, imperfections in the skin…all vastly affect the outcome.”

Tiny variations change outcomes, with impact within and beyond complex systems. “It’s hubris to think that we can control things from the top down,” Shoemaker points out. Eventually, top down decision-making – and a dose of hubris — led to the dramatic unraveling of Jurassic Park.

Shoemaker is further frustrated by how poorly scientific matters are related to the public. “I’m well aware that things don’t work well. I battle with science communication,” he says. To succeed as a landscape ecologist, he knows their work must be viewed by the public as relevant and relatable if a truly benign landscape can occur.

This brings Shoemaker back to modeling physical outcomes in demonstrable, tangible ways. It is a useful tool in the hands of a visionary, because the dynamic models they build are easily understood by those outside the scientific community. It is a tool for the common good, and can and does influence those beyond the Center’s halls.

The Center’s research, and Shoemaker’s passion, can shed light — and a better understanding — upon ecological matters for policy shapers and makers, and the public. And, infuse a healthy dose of hope.

North Carolina State University College of Natural Resources Center for Geospatial Analytics

As the technological and intellectual hub for the Chancellor’s Faculty Excellence Program in Geospatial Analytics, the Center for Geospatial Analytics ignites novel collaborations across several Colleges to advance geospatial frontiers.

Advancements in geospatial analytics are rapidly transforming science, society and decision-making by helping us understand spatial aspects of built and natural environments, and communicating location-aware information among people and places. The power of spatial computing is seen everywhere. Industry uses geospatial analytics for building site selection, mobile navigation, and asset tracking. Scientists use geospatial tools to track endangered species, predict infectious disease spread, monitor sea-level rise and understand global population dynamics. In the classroom,

students are learning new critical thinking skills to structure problems, find answers, and communicate solutions using the properties of space.

Read more from the Graduate School’s Think Magazine.

Download this article as a PDF.

- Categories: